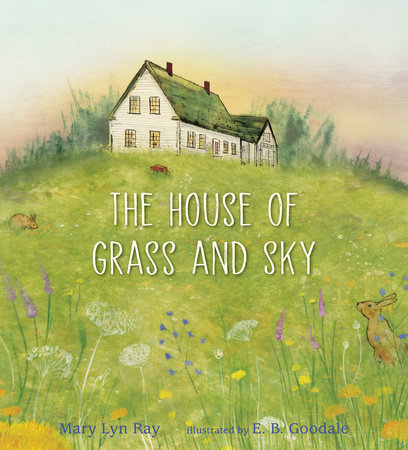

The House of Grass and Sky, illustrated by E. B. Goodale (Candlewick, 2021)

Once, out in the country, someone knew right where to build a house.

Inside it smelled of sunshine and new lumber. Outside smelled of meadow grass and sky.

This story is my valentine to the old New Hampshire farm and old New Hampshire house where, now many years back, I found I’d come home–as it is also a story for every house that waits to be a home.

Though there were many books I loved when I was growing up far from New England, that first book my mother read me when I was barely born become the one I loved best. Snow before Christmas, by Tasha Tudor, was about another old house on another old farm in New Hampshire, and I returned again and again to its spell. In time I began to imagine a similar house and farm I belonged to. I was certain they waited somewhere. And here, long years later, I found them.

In one room I discovered that a small drawer built into a wall had something written on the bottom in pencil. I looked closer and saw two letters. M.L. It seemed the house had known my name before I came. Like the family who arrive in the story, I felt as if maybe I had been expected.

The early Greek Revival cape where I live is not unlike (though not identical to) the house in this story. It’s now nearly a hundred and eighty years old. When I came, no one had lived here for forty years, and the house needed extreme repair. It had never had heat beyond woodstoves, or electricity, or indoor plumbing. I would add those, but I wanted to keep it an old house with old memory in it. I wanted to preserve its repose. And I wanted to honor what someone who built it understood and got right. I didn’t want to change it. I would fit myself to the house instead, letting it teach me how to be here. And it continues to.

The house in the story has always had a family, until one day it doesn’t. The house is certain one will come. But it must wait. Days and years and seasons pass. “[T]he moon still visits often. The house knows the moon, the moon knows the house. They are old friends. Yet the house can’t help remembering when children stood in rugs of moonlight and looked out at the night. And it wishes.”

Then? Sometimes wishes happen.

The Friendship Book, illustrated by Stephanie Graegin (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2019)

Sometimes being friends begins all at once.

And sometimes it takes awhile to get acquainted.

But then, as some small knowing grows, you start feeling that feeling that comes with having a friend.

This may be a first book about friendship and having (and being) a friend. But I like to think it’s as true for celebrating friendships of many, many years. It’s for anyone who has a friend or wants one. And it’s a reminder, too, that “a tree can be a friend. So can a rock you like to sit on or a lake or pond or grassy hill or some green mossy place. A dog or cat or nuzzly horse can, too.”

Though this book grew from The Thank You Book, in gratitude for what friends confer on our lives, it began with my very first friends, Sharon Brown and Kathy Davis . . . and a neighbor’s small dog named Snowball, with whom, at two, I liked to share an ice cream cone.

The Thank You Book, illustrated by Stephanie Graegin (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2018)

Thank you isn’t just for learning manners.

It’s also for when something makes a little hum–a happy little hum–inside you and you went to answer back.

Even very young, we know that happy little hum but we may not, then, have a name for it (or think to put a name to it). Or we may not know how to answer. Thank you becomes a way to.

Twined around a child’s day and year and occasions, this book invites noticing all the ways and times we feel that hum. It celebrates glue and glitter, laps and books, hands to hold, swings and slides, zippers that zip jackets when warm days turn cold, birthday cake and birthdays, puddles and parades, grass and toes, “and all that makes us wonder”–as well as this earth we ride on (and the stars beyond), family and home, bathtub ducks and bubblebath, and knowing “morning will come after night.” Thank you is for what is big and what is small and what is in-between, and “all we feel inside us that makes us glad that we are us.”

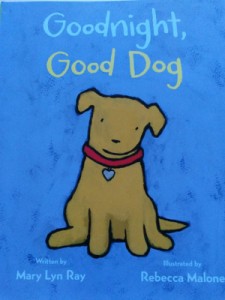

Goodnight, Good Dog, illustrated by Rebecca Malone (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2015)

The dog knows the click of the lamp when the light is turned off. He knows the sounds the dark makes. Those small night sounds. He knows the shadows in corners of rooms.

It’s bedtime, but this little dog isn’t sleepy. He remembers his day, he remembers his toys, he checks out the quiet, quiet house.

But he isn’t ready for bed–even his bed “round like the moon”–until he has the idea of dreaming back sun and grass and a new day.

The story had its beginnings when, every night, my new puppy–full of Westiness–wasn’t reconciled to being tucked in; but I hope it may offer some companionship to a reluctant child, too.

The years that I was growing up, my family was not a dog family. Whenever my mother, frustrated by something we’d done or not done, said to my sister or me, “I wish I’d raised cocker spaniels instead,” we knew we were testing her limits and had better be careful, because we knew she had no affection for cocker spaniels.

Over time, however, we all came to see that life with a dog is so much fuller than life without a dog. Each who has entered my life has bestowed on it blessings beyond enumeration–even when this same little puppy believed that the way to read a book was to chew it, and he was a committed reader.

I am happy to report that when I received the first copy of this book, I read it to him at bedtime and guess what? At first, he sat there and cocked his head. This was a story he understood, with words he knew! Like “come” and “good dog” and “goodnight, good dog.” Ears up and attentive, he studied each page I showed him–until we got to “So the dog makes himself snug and says to himself . . . “ Then he couldn’t help it: he lay down, curled himself into a ball, and before the end of the story was asleep.

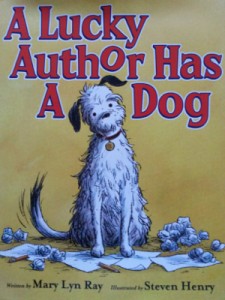

A Lucky Author Has a Dog, illustrated by Steven Henry (Arthur A. Levine, 2015)

Early in the morning, people are waking and going to work. So a dog is, too. Because an author should also be waking.

A look at an author’s day–and the ways a dog makes an author lucky. But a dog may also be lucky to have an author. Because “an author doesn’t say goodbye and go out the door to go to work. The author just takes a piece of paper and begins to write–and write and write . . . “

A visit to a school on Author’s Day, where everyone is an author, too, alters the usual habits of author and dog. But then? “Someone has waited all day for the click of the door. And now the author is home, smelling of school and its mysteries. For a moment there’s only author and dog,” then a walk–and more story to discover. “The dog will show the author how to look and listen the way a dog does. An author without a dog can learn. But having a dog is better. Because everything is better with a dog.”

Stories are all around us, waiting to be noticed. They poke up like the dandelion growing in a crack in a sidewalk, or the piece of blue glass found one day, or a feather in the grass, or what you were thinking at breakfast, or something someone said. Look for them and you’ll be lucky, too.

A Violin for Elva, illustrated by Tricia Tusa (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2015)

Above the ruffle of talk and the rustle of dresses, Elva heard music.

From the time she first hears it, Elva knows what she wants. But her parents say no. So she pretends a violin–until, grown up and busy with life, she almost surrenders what she has dreamed of. Except the longing won’t go away. So one day she “takes a breath and takes her purse” and, at last, buys a violin . . . then discovers it’s not so easy to play. Again she almost gives up. But with lessons and lots of practice (which her loyal dog endures), she perseveres until she is making the music she had always imagined.

In Elva’s story there’s recognition of a secret we each carry in us–some secret about who we are or something we want to give ourselves to–and reminder of what can come of saying yes (as well as some encouragement that it’s never too late for that yes).

Like Elva, I wanted to make music. Instead of playing school or playing bride, I played “Piano Lessons” until I could have actual lessons. I would convince my mother to go into Reed’s Music Store whenever we went downtown shopping, so I could be nearer what held music. I dreamed of a new piano; but, like Elva, I also wanted to play the violin and felt that same shivery feeling Elva felt when she looked at violin music.

Though a piano came first, I still promised myself that one day there would be a violin. For me, however, it happened differently from the way it happened for Elva. After telling someone I’d just met, appropriately named Angela, I suddenly had one. Her brother, it turned out, had died and left her his violin, and she had been looking for the right person to receive it. Learning how to play, and getting those first notes right–hearing wood and string resonate with song–was, I discovered, very like getting a word right on paper and then a whole story.

That was many years ago. I still pick up the violin. But the piano, I should admit, has won out. It is, for me, what a violin was for Elva. Both, however, are about the same thing.

Go to Sleep, Little Farm, illustrated by Christopher Silas Neal (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2014), now available also in a padded boardbook edition

Somewhere a bee makes a bed in a rose, because the bee knows day has come to a close.

Somewhere a beaver weaves a bed in a bog.

Somewhere a bear finds a bed in a log.

Night comes to forest and farm, as stars come out and dreams flicker near and a child is also tucked in.

Having learned here, where fields give way to forest, the habits of beaver, bear, fox and owl, “cows and horses on the hill,” and chickens that “roost where chickens will,” I’ve seen how our several worlds intersect and that’s where this began.

As much as I love the bright hours, my favorite time is when the day grows still and the sky starts to fade and dusk spreads. The mountains change from afternoon’s blue to twilight’s successions of lavender, then one by one stars come out, and the mysteries of night wrap around. All that seemed to ask for a story. And I wanted to find language quiet enough to tell it.

Deer Dancer, illustrated by Lauren Stringer (Beach Lane Books, 2014)

There’s a place I go that’s green and grass, a place I thought that no one knew–until the day a deer came.

A chance encounter with a deer becomes an invitation into the mysteries around us–and to dance.

At the just-before-dark time of day wonderfully called the gloaming, I like to sit on the doorstep and watch for the deer who graze in the field. But one evening, instead, I was standing out in the field when a single deer approached, coming as near as this one. It felt like some visitation–and felt, too, as if the deer had brought a story. But what was it?

Time went by and a friend who had taught dance was telling me how she’d helped her students learn a dancer’s posture. She had told them, “Hold your head as if you’re wearing antlers.” I immediately took that from her!–and knew then what the story wanted to be.

Oddly, I wasn’t remembering something else. If wanting to be a writer was the big secret I knew myself by, growing up, there was another secret, too. Whenever my mother and I went, after Reed’s, to the bookstore downtown, I went right to a book I hoped was still there–a book about ballet. Because I also wanted to be a dancer.

I could have had the book; it didn’t have to be a secret. But I wasn’t ready to tell. And I wasn’t, anyway, a likely dancer. The rhythm band box that every teacher brought out mystified me. And in third grade, I was the only one who couldn’t get my feet right when, each day, Miss Lipscomb put a record on the boxy phonograph and made us march around the room before we returned to our desks after lunch.

So I kept this secret close to me for many years–until one day, after I’d become a writer and was reaching for words for something I was trying to say, I suddenly felt as if I was dancing. Song filled me, and everything in me answered. And that’s how it continues to feel when I’m writing.

Some of us know what we want to be when we grow up, and then we do that as soon as we are grown-up. Others of us have to carry that dream or that wanting a long time, while we find our way to it. In each of us, however, there is some secret we hold onto–about who we are or something we want to give ourselves to. What matters is not to forget that, and then to allow it to happen.

Boom! illustrated by Steven Salerno (Disney, 2013)

Although Rosie was a small dog, she was usually very brave–just like the boy she knew best.

Herein, the trials (and comforts) of a dog who doesn’t like thunder.

This story was for my first dear and fearless Westie, who trembled only at thunder. But like the small dog of the story, she, too, when a storm had passed, “barked at the stillness, a brave dog again.”

Stars, illustrated by Marla Frazee (Beach Lane Books, 2011)

A star is how you know it’s almost night. As soon as you see one, there’s another, and another. And the dark that comes doesn’t feel so dark.

Of stars and all the places we might find them–and something of why they matter.

There are stars you can draw on shiny paper and stars that make a wand: “If you hold a wand the right way, you might see a wish come true. Not always. Only sometimes. You never know about a wish.” There are buttons with stars on them. There are white stars in the grass that become strawberries in July. “Blow a ball of dandelion, and you blow a thousand stars into the sky.” Then there are the stars that come with night . . .

Until I came here to this old New Hampshire farm, I had never seen the thousand thousand thousand stars of a country night. Nor had I seen so many falling stars (or shooting stars or whatever we choose to call them: sometimes I think of them as flying stars, in their glittery arcs). All of that came together, magically, when Marla and our editor were visiting, just when we’d decided to make this book. Late at night, we were standing outside, under the wonder of night, and a spectacular star spun across the sky. It seemed a good sign–and was.

Christmas Farm, illustrated by Barry Root (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2008)

Wilma had grown petunias and sunflowers for years. She was ready to graduate to something else. But she couldn’t decide what.

Wilma and her young neighbor, Parker, plant sixty-two dozen small balsam seedlings, then tend them as the boy and the trees grow into themselves, over the next five years, in a story of friendship and stewardship and Christmas trees.

When I was growing up in the South, most people cut a pine at Christmas. But my parents and sister and I went every year to the same city lot fragrant with rows of balsam trees brought by truck from Vermont or New Hampshire or Maine. Our Christmas would smell of New England–where I imagined an old, old farm sheltered by maples, visited by deer, bound by stonewalls and white hills and blue mountains. In the myth I’d early constructed, that was the place I belonged to . . . and now do, having incrementally found my way to New England, then New Hampshire, then this farm where, every July, I climb the hill behind this house of long memory to visit the steep shade of balsams that grow there rooted in granite. It feels like where Christmas begins. And there, like Wilma, I choose a tree for December.

Christmas trees aren’t a quick crop. When set out on tree farms, a seedling is already five years old and typically requires at least five more years before cutting. These seedlings ensure, however, a renewable and conscionable supply of trees and, in many instances, allow farmers to make use of land that can’t carry other crops. But tree farms don’t provide only Christmas trees. They are rich habitat for animals and birds and wildflowers and bees. And their green rows remind us, too, that the year will come again to December and the ancient mysteries that December brings us to.

Welcome, Brown Bird, illustrated by Peter Sylvada (Harcourt, 2004)

A boy lived at the edge of a hemlock woods. In March he watched the snow melt. In April he saw the grass grow green. Then he began to listen.

On a northern farm, a boy waits for the song that announces the return of the wood thrush, which means, as well, the return of spring. Then all summer he “honors it by listening” (while also protecting its habitat)–until fall comes and far away in a rain forest, another boy is welcoming back la flauta. As fall turns to winter, and winter turns to spring, he, too, honors it by listening and protecting where it dwells–until one day the thrush is not there. But now, away to the north, a boy hears again that the thrush is back. “Neither boy knew where the brown bird went. Only the bird knew they were brothers.”

It used to be that, every April, I waited for when wood thrush and hermit thrush returned with their “silvery, circular song.” Now it’s if.

At both ends of their migration route–in North America and Central or South America–habitat for thrushes and other songbirds is being lost, more and more, to change and development. Nesting sites are disappearing, shelter and food sources are disappearing, predation by other birds and animals is more likely. And, of all songbirds, the thrushes are most threatened. Already they are listed as endangered, and every year there is less thrush song.

When I signed a conservation easement for this old farm in New Hampshire, I thought I was preserving land. Now I see I was also protecting song. But random parcels aren’t enough. Wherever we want to hear thrushes and other birds continue to sing, we will have to find ways of integrating habitat for ourselves and them.

All Aboard, illustrated by Amiko Hirao (Little, Brown, 2002)

Long train, silver train. Long train, silver train.

Long train. Long train. Silver train. Silver train.

Train, train, train, train.

Whooo whoooooo.

My valentine to trains.

School visits have taken me around the country, and most invitations I decide by whether or not I can get somewhere by train. I love the roll of the train, its enclosed world, the tiny bedroom and tiny sink, the conversations on trains and meals in the dining car; but most of all I love that continuous passage across the landscape, all night and all day: that between. I’m looking out the window, just taking in what there is to see–and writing. One of my favorite places to write is on a train, and there’s the bonus that a train often goes on the backside of places, revealing a story different from the one in front.

Red Rubber Boot Day, illustrated by Lauren Stringer (Harcourt, 2000)

I press my nose against the screen and smell the smell of screen and rain.

What makes a day for boots and puddles a day to savor.

I’ve always loved a day of rain–a day for being inside, and outside. I suppose I should admit I’ve, also, always liked puddles.

In this second book illustrated by Lauren Stringer (Deer Dancer is a wonderful third), look for a small homage to the first one, Mud.

Basket Moon, illustrated by Barbara Cooney (Little, Brown, 1999)

The moon was almost round. The Basket Moon. Pa would be going to Hudson.

Of baskets and basketmaking and coming of age and recognizing what matters. Based on the true stories of a community of basketmakers in the Taghkanic area of New York around 1900.

Although Taghkanic baskets were handsome and enduring, the basketmakers were mocked as backwoods hillbillies and bushwhackers. To write this, I had to learn how to tell the truth of their story without sacrificing what was lyric in it to what shadowed it. That took many attempts, but in getting there, I also learned to put a name on what I most want to give place to in picture books: song (or something close to it) and what the song comes from.

Mud, illustrated by Lauren Stringer (Harcourt Brace, 1996)

One night it happens.

A celebration of winter melting into spring, which also means MUD.

One New Hampshire night in March I smelled again that annual smell that announces thaw: that “cold sweet smell” that rises from the earth. I remembered again how spring comes. I remembered mud. I remembered how I grew up liking mud, squeezing mud between my toes, drawing rivers with a stick, making mudpies and fairy dishes. But I also remembered how it seemed I had never really known mud until I experienced my first March here. And suddenly there was the story.

Shaker Boy, illustrated by Jeannette Winter (Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1994)

When Caleb Whitcher came to live with the Shakers, he suddenly acquired 141 brothers and 138 sisters. He had never seen such an unusual family, or such an unusual house.

A life among the Shakers, beginning with Caleb’s arrival c. 1860, told around Shaker songs.

I’ve long admired the economy that informed the Shaker aesthetic–and in the spare lines of their furniture I see something similar to the paring that shapes a picture book.

My Winterthur thesis was a reappraisal of Shaker design and culture and, in my museum life, I had curated two exhibitions of Shaker furniture, then studied closely the Canterbury (N.H.) Shaker community. All of that provided the base for this story, and original manuscripts and songs helped fill it out.

Alvah and Arvilla, illustrated by Barry Root (Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1994)

Arvilla was canning peaches when she got the idea. She filled the jars, put on the lids, and took them to the cellar, where she stored pickles and preserves for winter.

Upstairs, she cleared the kitchen, made supper, and called Alvah.

The idea didn’t go away.

When neighbors in Danbury had to come home from their honeymoon to milk their cows, I felt there should have been a way for them to have a longer wedding trip. This is the story that came in answer.

Time shifts backwards to around 1900, and Donna and Phil become Arvilla and Alvah, who have been married thirty-one years. And for those thirty-one years Arvilla has wanted to go on a trip to see the Pacific Ocean–“a trip like their neighbors took, one you could send postcards from.” But for thirty-one years Alvah has said “You can’t have a farm and travel,” until Arvilla replies, “If it’s the animals keeping us home, we could take the animals with us.”

So they do.

Pianna, illustrated by Bobbie Henba (Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1994)

Anna’s father built a house between the railroad and Ragged Mountain.

This is the true story of a So. Danbury neighbor whose parents observed she was “musical” when, returning from a Grange program, she went to the organ in the parlor and, “pumping with one foot, . . . stood there and played what she had heard at the show.” (I knew all about the one-foot part. If your legs are too short to reach the pedals, that’s what you do. When I was growing up, my father had taught me to play our antique pump organ, while standing beside me to pump. But if he wasn’t there, I’d had to make-do.)

When my neighbor’s parents bought her a piano, which arrived by train, no one else in town had one, and no one could give her lessons. So, to learn to play, every Saturday Anna (as she’s called in the story) rode the same train to Boston, a hundred seven and a half miles down, and a hundred seven and a half miles back. In the piano she has met what will be with her all her life. Even after she marries, the music she finds there remains essential to her: “She played with a baby on her lap. She played while it napped. She played while the clothes dried. She played while the bread rose, while the stove heated, while the cow grazed. She played while beans bloomed in the garden, while the bright leaves fell, while snowpiles grew against the pumpkin-colored house . . . “

And when I met her, she played for me.

A Rumbly Tumbly Glittery Gritty Place, illustrated by Douglas Florian (Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1993)

Across the road there is a gravel pit. It is a place to watch machines in: loaders, shovels, dozers. Some grown-ups think it’s ugly. But I know different.

A valentine to a gravel pit, to “a billion billion billion rocks. Gray rocks, brown rocks, pink rocks, shiny rocks,” to “a beach without an ocean” . . .

When I bought this farm, I found myself also owning a no longer active gravel pit. It was a raw place. But still I went there to walk. I went there to think in the big blankness of sand–which, I began to see, wasn’t blank. And slowly I learned an affection for it. I filled my pockets with rocks that I lined up on windowsills. I noticed sand gardens. I refocused my eye to the scale of sand grains. Then one day this story came and I was reminded by the voice of a child of what we may outgrow childhood and forget: how to love the world as it is.

The same machines that had dug out the gravel pit eventually smoothed the cuts. Now it’s a hayfield again. When my neighbor brings his tractor to mow and I sit on the wide boards of his trailer, my dock in a timothy sea, I am surrounded by green. Then John and the tractor begin their broad circuits, the mowing and raking begin, and across long, warm afternoons, I listen to the baling. Thunka thunka thunk. It is the sound of summer.

Pumpkins, illustrated by Barry Root (Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1992)

Once upon a time there was a field. It was a particular field in a particular place, where it lived among young hills that would grow up to be mountains.

Pumpkins (461,212 to be exact) provide a way to save a field–and keep the idea going. There’s a lot of my own story in this, except I didn’t actually plant pumpkins: the books have become my pumpkins. In a picture book, however, a story usually has to find resolution in twenty-eight or twenty-nine pages. Real life can take longer.

In efforts to protect places that matter to them, readers have affirmed again and again the last lines of the story: “Somewhere, someone might love another field pumpkins could save.” Unmatched, however, is a then-third grade reader who by herself grew pumpkins, sold them at a local farmers’ market along with pumpkin bread, gave the money she earned to her town to help buy conservation land–and year after year has kept on.

And the field the story was written for?

When heirs sold this classic Greek Revival farmhouse to me, they attached five acres and kept the surrounding hundred-and-sixty in their purse. Land prices were going up and up, as much of New Hampshire’s historical landscape was being lost to development. And a developer was courting the heirs. So when they decided the time had come to sell those remaining acres and offered me first refusal, I knew I had to buy the land. I didn’t want to lose this green quiet or what I saw outside every window. But I wasn’t wanting just to shield what I lived with. I wanted what was here to still be here not only for me but for generations after and all those who pause here now. I wanted it for deer and trees and grasses, for bluebirds and redwings and thrushes, for moose and salamanders, for milkweed, for monarchs and September asters, for all that is remembered and renewed here. I wanted to preserve a habitat for those mysteries I’ve met here. And I wanted, as much, to rejoin the farm to the house. I wanted to keep that memory in the land: This is what a farm was, and here was a landscape of farms like this one. The history of this place is held in that memory, and the history matters for all the reasons it matters to remember who we’ve been, and why.

What I didn’t know was how I would pay for it.

No one had lived here for forty years, the windows were splintered, the chimneys had crumbled, and there had never been electricity or running water or heat except for a couple of stoves. Room by room, I was reclaiming the house, while leaving it still an old house with old memories in it. Any money I’d begun with had gone already to new roof, new windows, well, electricity, plumbing, furnace, chimneys, paint. And that work wasn’t done. Yet I couldn’t let the farm become condos.

My sister knew what I felt for the land, as she also knew my purse was empty. But being four years older and four years smarter, she said, “You could always plant pumpkins.” And, as smartly, I answered, “It would be easier to write a story about a man who plants pumpkins.” The one problem: I’d believed since second grade that I couldn’t write stories. I didn’t expect to, then. But that night, when I was about to take a bath and water was splashing into the bathtub, these words swam across my head: Once upon a time there was a field. It was a particular field in a particular place, where it lived among young hills that would grow up to be mountains. I couldn’t deny that sounded like the start of a story. So I went and got paper and started writing.

I didn’t know then that the story would have a public life. I thought it was just for me, to help me believe I could find a way. And books, anyway, aren’t so quick as pumpkins.

Gravel left by a long-ago glacier, and the old gravel pit, seemed to offer a more immediate answer. A bank would accept that collateral and I, the Great Conservationist, reluctantly agreed: operating even a modest strip mine is hardly standard conservation practice. With the bank’s money, I bought the land and signed a conservation easement–adding a period of time for removing enough of the gravel before reclaiming the entire area. It turned out, however, that an engineer’s appraisal had been false. There was almost no gravel to sell. What I had instead was a protected farm and a bank loan I had no way of repaying.

Although picture books have become my pumpkins, they are slower, just as the story of a life is larger and more complex than a story that fits in a picture book. Getting by has been iffy. I’ve learned what choices cost. But when I look at timothy blowing in waves across the field and, in this country quiet, can hear at night all the way to the stars, I wouldn’t undo what I chose.